Introduction

During the Second Dynasty on Tarnus, a counselor of the Ganash invented a board game, or more properly a table game, which evolved and soon became the obsession of three colls through the beginning of the Third Dynasty. This is the game of MuTou, or ‘Boiling Stone’, a strategy and gambling game which has no parallel anywhere in Tarnus history. Colls with communities on the surface of Tarnus, particularly in the areas farthest from the underground cities, still hold long and elaborate MuTou gatherings every year.

This essay describes only the basics of the game. Many of its more florid features and characteristics are omitted here, and may be found in near-complete form in Yinzaimarr‘s “MuTou: A Cultural, Ideological, and Mathematical History.” Unfortunately, Yinzaimarr has become rather outdated since its publication over fifty years ago, and nothing has been done to bring it up to date. Durinnal‘s popular “Ten Days of MuTou", to the serious student of the game, is simply worthless.

Translator’s Note

In the description that follows, some of the terms have been translated from their Share and Clang forms to English, and others have been allowed to stand as they are normally pronounced. Some few forms, like ‘tessel, tessels', preserve meaning across the translation and are left intact. Such terms as ‘board’, ‘move’, and ‘turn’ have been translated throughout, since the terms used by a coll are utterly different from their counterparts in other colls, and no coll‘s words for these terms have gained general use.

The terms ‘walker’, ‘angler’, ‘jagger', and ‘rand’ are translated adaptations that read much more easily in translation for English speakers than the common terms in Share. For example, ‘angler’ in English carries the implications of the direction and type of move quite nicely — why make matters more difficult by using the Share form ‘mirai-zaldji’, which is much too close to the term ‘mirau-zanji’ used for ‘rand’?

Tonal variations are not represented here, to keep the presentation simple, but those interested in Sinese influences on Clang will probably look further to find the relevant tones and tonal junctures. A brief glossary is provided at the end of this document for those who wish for a compact reference of the terms used here.

MuTou and Chess

To describe the game, let’s compare it with chess, a game of renown on ancient Earth. MuTou resembles chess in that it uses pieces that move in different ways, and it is played on a tesselated board or playing surface, but the resemblance from there on is quite limited.

Here are some of the salient differences:

- In chess, there are two opponents, each with pieces of fixed allegiance. In MuTou, there may be as many players as can manage to scramble into a game, and the allegiance of any piece may change.

- In chess, there is one winner, and one loser — the object of the game is to defeat one’s opponent. MuTou may be played this way, or it may be played to establish a balance among multiple players. In establishing the balance, the end of the game is determined by mutual consent of all participants. Since a stubborn player may unduly delay the balance, the tendency of other players to combine to eliminate that player’s pieces has a moderating effect on such recalcitrance.

- In chess, the pieces, with the exception of promoting pawns, do not change their moves or powers. In MuTou, the pieces may change their moves or powers at any time desired by the players, subject to certain constraints.

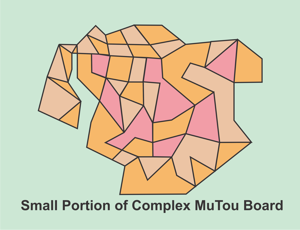

- In chess, the board remains the same size and shape, and the squares retain the same shape and connectedness. None of these attributes is true in MuTou; squares are only one possible shape for the places on which pieces may rest, and these places may be connected to one another in highly arbitrary fashion.

- In chess, one turn for one player means that one piece is moved once (except for castling). In MuTou, one turn for one player means that the player may move as many pieces as many times as that player’s available turn-energy allows. ‘Turn-energy’ refers to the number of wafers (darjarinn) on the player’s power piece (darj — see below).

- In chess, there is a single piece on each side, the king, which represents a player’s ‘life’. In MuTou, the player is free to diffuse the critical ‘life’ element, called the ‘blood’, among many pieces, so that to be vanquished, he or she or it must lose all of the pieces endowed with the blood. In more-advanced play, a player may be required to create interdependencies among the pieces bearing the blood, so that only the loss of any of several different sub-combinations of the pieces is necessary for loss of the game. In this mode, the exposures created by this tactic are compensated for by the fact that the player need not reveal the dependencies until forced to do so by the play of the game.

- In chess, moves are certain; the legal move a player makes is executed on the playing surface. In MuTou, the legal move a player makes may be modified, after the move is disclosed, by several carefully-defined circumstances of play.

- In chess, the circumstances of play remain fixed; that is, no factors of chance or undisclosed information exist in the game. In MuTou, both chance, in the form of die casts, and undisclosed information, in the form of players unmasking and comparing hidden choices, affect the play of the game.

- In chess the moves are made alternately and, particularly in competition, on a timed basis. In MuTou, the moves in a turn are performed in a rhythm, to music, usually alternately or (if there are more than two players) cyclically; but if a player fails to complete the moves to be made in one turn, the next player to move may begin moving pieces, and may indeed disrupt the previous player’s moves that were overrun.

These are general points of contrast. They also make clear why one popular nickname for MuTou is ‘madness’, (kuangren). See the section on Social Dimensions of the Game.

The Pieces

Pieces in MuTou are of three types: board pieces, power pieces, and choice pieces, called respectively Anjia, Darjia, and Quandarinn. We’ll look at all three types.

Board Pieces (Anjia)

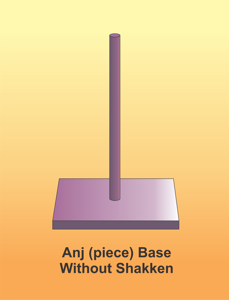

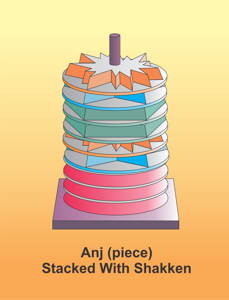

Each board piece (anj) has one fundamental unit, called either a ‘mast’ or a ‘basket’. A generic term for these two units is ‘base’. A base is a heavy block of metal used for grasping and moving, and for stacking the shakken (disks). A base by itself cannot move. It can only occupy a tessel (the equivalent of a chess ‘square’). A base may be captured and turned (which changes its allegiance), or else removed from the game.

The mast is a spike on the base’s heavy block of metal, tall enough to hold as many as ten articulated disks called ‘shakken' (singular ‘shak'). The basket is a set of four posts, also on a heavy block of metal, which can also hold a stack of up to ten shakken. A base may take either form. Shakken stack on the mast via a hole in the center of each one, and stack in a basket by being retained by its posts.

Atop the stack of shakken a player places one’s ‘noejj', an identifying cone, showing the piece’s allegiance, that remains on the piece until its allegiance changes to that of another player.

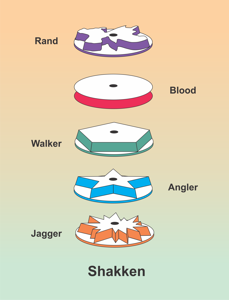

The shakken come in the following forms:

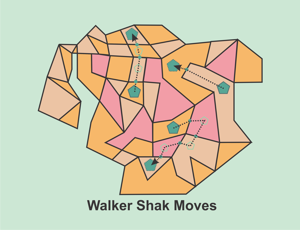

Walker

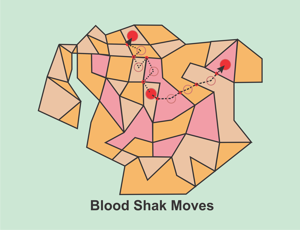

The Walker shak empowers the base with the ability to move from its current tessel to any tessel sharing an edge with it. The analogous chess move is a rook’s move to an adjacent square. The board segment at right shows a few possible Walker moves across the edges of the tessels.

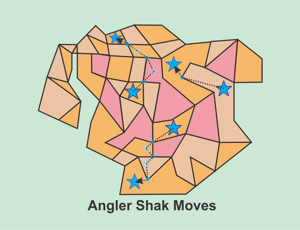

Angler

The Angler shak empowers the base with the ability to move from its current tessel to any tessel sharing a vertex with it (except one sharing an edge). The most-nearly-analogous chess move is a bishop’s move to a diagonally-adjacent square. When two tessels share multiple vertices without sharing an edge, the angler’s move applies to such tessels.

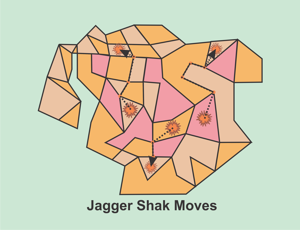

The Jagger move sounds complicated, but it isn’t hard to visualize or execute once it is understood. The Jagger shak on a base empowers the base with the ability to move from its current tessel to any tessel sharing neither an edge nor a vertex with it, but reachable solely by tracing a single edge from a vertex of the current tessel, between two adjacent tessels (neither of them the current one), to the next vertex not on the current tessel, and onto a tessel sharing that vertex but not sharing an edge with the path taken to that vertex. A careful look at the image here shows how the Jagger move takes the piece along the edge of an intervening tessel. There is no exactly-analogous chess move, but a knight’s move qualifies as a single-edge Jagger move. If chess had a piece which could skip over a square, moving like a rook, that piece would also be moving as a Jagger would dictate.

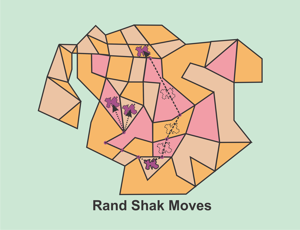

Rand

Rand, empowering the base with the ability to move from its current tessel to a tessel determined completely by the use of the quandarinn (choice pieces; see below). To do this, two players, the one moving just before and the one moving just after the player making this move, use one quandar each. The prior-moving player selects any vertex, then rolls the quandar and counts edge, vertex, edge, vertex alternately in either direction around the piece’s tessel from the selected vertex. The next-moving player then rolls the other quandar; if the first count landed on a vertex, the number of vertices is counted and the piece is moved to the farthest tessel reachable via that number of vertices; if the first count landed on an edge, the number of edges is counted and the piece is moved to the farthest tessel reachable via that number of edges. If there are only two players, clearly, the next-moving and prior-moving players are the same one. The ‘farthest’ tessel is determined by comparing shortest-path lengths between candidate tessels, and choosing the tessel with the longest shortest-path length. If two tessels meet the same criterion for ‘farthest’, the player making the move may choose between them. There is, obviously, no exactly-analogous chess move.

Blood

Blood, indicating that capture, removal or change of allegiance of this piece reduces the owning player’s survivability in the game. Loss of the last piece carrying a player’s blood shak forces that player from the game. A Blood shak empowers the piece with the moves of both the Walker and the Angler. Analogous in chess is the king’s move, or if more than one Walker or Angler shak is stacked, a limited length of the queen’s move.

A player may use the shak‘s move as many times as the shak appears on the base. Thus if a base carries three Walkers, three Anglers and four Jaggers, the controlling player may, in one move, perform three Walker moves, three Angler moves, and four Jagger moves, in any permutation of order. Each Walker move, consisting of the crossing of a tessel edge, costs one move unit. Each Angler move, consisting of the crossing of one tessel vertex, costs one move unit. Each Jagger move, consisting of the tracing along one tessel edge, costs one move unit (the transits of the vertices for the start and end of the Jagger move of the tessel have no cost). Since every base can carry no more than ten shakken, every piece is restricted in its range for each move to a maximum of ten move units. The actual number of move units usable in one turn is also subject to power piece restrictions (see below). If a player’s power piece allows for a maximum of fewer than ten move units during a single turn, no piece can exceed that maximum in a turn.

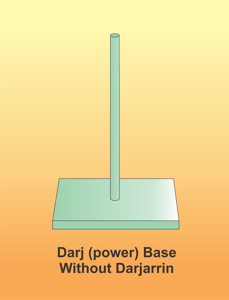

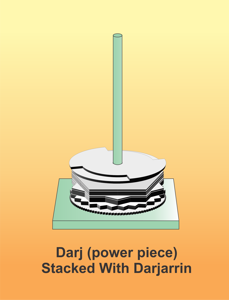

Power Pieces (Darjia)

Each player owns a single power piece (darj), which resembles the board piece in that it has a base with a basket or a mast. The power piece carries a stack of wafers (darjarinn), the height of which represents the player’s number of move units usable during a single move. When a player is defeated in a game, all of that player’s darjarinn go to the one who captured or changed the allegiance of the defeated player’s last blood shak. All players begin play with equal numbers of darjarinn on their power pieces.

The number of darjarinn on a player’s power piece may change during the game; a player may gain or lose darjarinn during a game, depending on the carrying out of certain actions. Yielding a complete turn (without moving) gains a darjarr. Making an extra move (one or more move units applied for a piece not already moved, or for a piece for which all move units had already been applied) during a turn loses a darjarr. Countering another player’s move with a choice loses a darjarr to the countered player. Defeat takes all of a player’s darjarinn from one’s darj.

It is important to distinguish between darjarinn and wafer-points, or addarjaki (s. darjanka). A darjarr is a more-or-less-permanent object in a player’s possession, resting on the player’s darj. A darjanka refers to the unit value of a darjarr on the darj when counting moves during a player’s turn.

The number of darjarinn to be used is agreed on by all players at the outset. A friendly game usually uses only a few darjarinn; a high-stakes, coll-to-coll game usually uses as many as the players dare. The total number of darjarinn available for play is also set; if a player gains entitlement to an additional darjarr and none are available, the entitlement is ‘banked’ until another darjarr is made available AND the player receives a new entitlement. When these conditions are met, the player receives the darjarr gained from the new entitlement and the darjarr cashed from the banked entitlement, two darjarinn in all. If more than one player has banked entitlements, there is no particular ordering of their cashing from the bank; the first player with banked entitlements to gain a new one is the first to cash an entitlement one has banked.

Choice Pieces (Quandarinn)

These are small dice-like polyhedra, called quandarinn, shared by all players. Each facet of each quandar is inscribed with a different number, from one up to the number of facets on the quandar. At the conclusion of any move within a player’s turn, any player may call for a choice, either by an open toss of one quandar or the simultaneous uncovering and matching of two quandarinn by the caller and the called player. If one quandar is used, the number showing atop the quandar gives the quandar total; if two quandarinn are matched, the positive difference of the two gives the quandar total. The choice alters the outcome of the move, and costs the caller one darjarr. This darjarr is removed immediately from the caller’s power piece and added to the called player’s power piece.

The Appearance and Functioning of Pieces

In designing a full set of the anjia, the darjia, and the quandarinn, together with the shakken, noejjaim, and darjarinn that combine with them, the colls exercise great craft, artisanship, and engineering. Standard dimensions are paramount. The first basic requirement is that any anj must be able to stack any shak and noejj, and any darj must be able to stack any darjarinn, no matter which coll and which piece set is involved. Second, all shakken, noejjaim, and darjarinn must be of standard size and shape. Third, coll colors for a given noejj must be plainly visible to all players at all times on the noejj surface. Fourth, all shakken and darjarinn in play must be clearly visible to all players at all times.

The designs of the anjia and darjia and their stackable components vary tremendously from coll to coll, and from designer to designer. Most are made of steel, fabricated with mast or basket of steel, and cast or worked on the surface into complex patterns usually incorporating coll inscriptions. Colors often adorn the metal, whether as inlays or as surface treatments. Some sets use microfabrication technology to place patterns of working circuitry on each piece; some sets display deposited gem materials such as sapphire or ruby; some use multiple methods of surface adornment and activation.

The Playing Area

The game is played on a table or surface of any size. The surface must be prepared for the game by layering it with material which allows the inscribing of the tessels and the labeling both of initial stands for all players and of tessel edge splices. Each player will scribe out an area of tessels called the ‘stand’, with all of its tessels edge-contiguous, and places all of one’s pieces in that area, each piece configured as one desires. The scribing of the tessels lying between the stands is done by all players, according to certain restrictions.

Each tessel must have identifiable vertices, identifiable edges, and a single, identifiable, connected area. Each tessel must have at least one edge, and all edges must be connected end-to-end, at the tessel‘s vertices, into a closed, orientable, two-dimensional surface comprising the area (an infamous attempt by an Arcus Junusium player to create a non-orientable playing surface like a Möbius strip in one game triggered the addition of the orientability requirement). The number of vertices, and therefore the number of edges, cannot exceed nineteen for any tessel (this restriction arose when a Fandarinn player tried to define a tessel mathematically as having an infinite series of edges approaching a vertex asymptotically).

Note that the boundary between two tessels may comprise one, two, or more edges with their bounding vertices. When counting a Jagger move along such a boundary, a player must count as a move unit each traversal of a vertex.

Turns And Moves

The players take turns in cyclical order, one by one, in rhythm to the music, starting with an elected player. Each turn, for a player, is carried out as follows:

The player chooses whether to move or to rest. If no move is made, a wafer is added to the player’s power piece, and the move passes to the next player.

If the player chooses to move, one counts the darjarinn in one’s power piece to get a total of wafer-points (addarjaki), and then chooses whether to move one or more pieces, alter one or more pieces, or alter the playing area. These choices are mutually exclusive in the basic game; in the advanced game, they may be mixed.

If moving pieces, the player moves as many times as one’s total of addarjaki. Each use of a shak counts as a move. Any number of pieces, up to the number of addarjaki, may be moved, and any single piece may be moved as many times as the number of addarjaki. A series of moves may freely revisit tessels or cross the path of earlier moves in the player’s turn. If, on a move, a choice is called, the piece just moved is moved again as if a Rand shak had been applied, as many times as the quandar total.

If altering pieces, the player moves a shak from one piece to another as many times as one’s total of addarjaki. Each single move of a shak from one piece to a piece on an edge– or vertex-neighboring tessel, counts as one alteration. If the tessels of the two pieces involved are not adjacent, one additional alteration must be counted for every vertex or edge on the shortest connecting path of the two tessels. An alteration may be undone and redone more than once, as long as the full wafer count is applied. If, on an alteration, a choice is called, the moving player casts the shakken of the two pieces involved into a single heap; the calling player then selects up to as many of the shakken as the quandar total, and distributes them between the two pieces; the called player then distributes any remaining shakken between the two pieces.

If altering the playing area, the player carries out as many alterations as one’s total of addarjaki. A player may alter only tessels on which that player’s pieces stand, or tessels adjoining such tessels at either an edge or a vertex. The alterations possible are:

- Adding a tessel to the playing area. This costs one wafer-point (darjanka). A tessel may be added by adjoining either an edge and two vertices, or one vertex, to the tessel occupied by any of the player’s pieces.

- Removing a tessel from the playing area. This costs one darjanka. An embedded tessel may be removed; the edges of the vacated space become edges of the playing surface.

- Combining two tessels that share one edge into a single tessel (one of the tessels must be unoccupied). This costs one darjanka.

- Splitting a tessel into two (if the tessel is occupied, the player may choose on which tessel to place it). This costs one darjanka. The splitting player may choose the locations of the vertices of the split.

- Splicing a tessel to another by relabeling its edge and that of the other tessel. The tessels being spliced may be remote from each other, but the player splicing must have a piece occupying both tessels to perform the splice. Splicing costs two addarjaki plus the same number of darjarinn as there are tessels between the two being spliced, counted as the smallest number of vertices crossed between the two being spliced, not using any splices in the count. The edge spliced may not be crossed to or from the formerly-adjoining tessel, nor may the vertices at the ends of that edge be used to reach edges of the formerly-adjoining tessel. If the edge of the tessel is at the edge of the scribed playing surface, it may be spliced to a tessel at another tessel edge at the edge of the playing surface at a cost of two addarjaki.

- Severing a tessel splice. Severing costs two addarjaki plus the same number of darjarinn as there are tessels between the two being severed, not using any splices in the count. Severing a splice restores connectivity between a just-unspliced tessel and the physically-adjoining tessel on the severed edge.

- Null-splicing a tessel, by labeling one of its edges as a barrier (which functions just the same way as the normal edge of the playing surface). Null-splicing costs one wafer. The edge null-spliced may not be crossed to or from the formerly-adjoining tessel, nor may the vertices at the ends of that edge be used to reach edges of the formerly-adjoining tessel.

- Severing a null-splice, restoring connectivity between a just-unspliced tessel and the physically-adjoining tessel on the severed edge. Severing a null-splice costs one wafer.

- Adding a vertex to an edge, or deleting a vertex from an edge, costing one darjanka.

If, on a playing-area alteration move, a choice is called, the calling player may interpolate up to the quandar total of additional playing-area alteration moves, of the calling player’s choice, in the called player’s move sequence as it stands at the time of the call.

In some advanced forms of the game, the number of darjarinn per player is higher, and the usage of darjarinn may be freely distributed among the three types of move.

Play

The play of the game consists of the following stages:

- Setting the order of play

- Configuring the pieces

- Scribing the playing area

- Setting out the pieces

- Conducting the play of the turns

The Order Of Play

Before doing anything else, the players establish the sequence in which they will take turns. This process is outside the game itself; it is usually set by either seniority of age, seniority of experience in the game, game ability, or player social rank.

Configuration of The Pieces

MuTou has several different tiers of play; the tier of play selected by the players for a given game dictates the numbers of board pieces, shakken and darjarinn to be set out at the start. Here are the totals for each level of play:

| Level of Play | Horse | Rapid | Black | Family | Lun | Coll |

| Shakken | 6 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 36 | 48 |

| Walkers | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 18 | 24 |

| Anglers | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 18 | 24 |

| Jaggers | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 18 | 24 |

| Rands | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 18 | 24 |

| Bloods | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 16 |

| Power-Piece Darjarinn | 3 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 18 | 24 |

If those playing so decide mutually, they can modify these initial totals as they see fit. Such adjustments must be agreed on by all players before continuing.

Scribing The Playing Area (Board)

When setting up the game, the playing area’s tessels must be drawn, or scribed, on the playing surface. The name MuTou, or ‘Boiling Stone’ comes from this process.

In casual or friendly games, one of the set layouts of the playing area is used. This saves much time and effort, and focuses the game on the play of the pieces. There are set layouts for two to ten players; often the playing surfaces are pre-scribed with tessels in a configuration which allows quick changes into one of the set layouts.

Actual scribing of an empty playing surface, required for all serious or significant games, requires the following steps:

Outlining: the first player in the order of play scribes the segment of the periphery of the area of play, marks a center-point for the area of play, and creates the areas, called zones, each of which contains at least sufficient space for a stand of as many tessels as a player has pieces in the game, for a single player. Note that no tessels have yet been created or marked; the area-creation process entails only the drawing of boundaries.

Cutting: each remaining player, in the order of play, claims a zone. The last unclaimed zone belongs to the first (outlining) player, who is not granted a choice.

Sowing: each players throw all of one’s shakken inside one’s zone, and tries to draw as many tessels in the zone as there are shakken to be cast, using the positions of the shakken as the centers of tessels, and scribing edges between adjacent shakken. If a shak is cast outside the zone, or lands atop another shak, it is cast again until it falls in an un-scribed area. Considerable creativity is used in the sowing stage; players can scribe elongated, stellated or other odd-shaped tessels that bound each other in unusual ways.

Tessels may be as large as desired, but every tessel must be of sufficient size to hold a base. Vacant spaces may be left between tessels, as long as each tessel is connected to the rest of the tessels in the playing space by at least one vertex. If an area is left open after the player is done scribing, the scribing player may leave it outside the playing area, or make it a tessel itself. Every player must scribe at least as many tessels as are needed for a stand of the initial count of pieces. A player may choose to draw no tessels besides those needed for the stand, the initial arraying of the pieces; in that case, the unscribed area becomes a single tessel (or possibly more than one, if the stand touches the border of the zone in more than one place).

The stand cannot be left isolated from the rest of the playing area; it must adjoin the remainder of the playing area by at least one vertex.

The connectedness of the playing surface is usually simple and two-dimensional, as on a chessboard. The scribing and alteration of playing surfaces into more complex forms is quite possible, and is in fact popular with certain colls and families. The remote-splicing of tessels is the means for establishing complex playing-surface connections among tessels and areas of tessels. The sole restriction is that the playing surface as a whole must be orientable, that is, the ‘underside’ of a tessel may not be added to the playing surface, either by remote-splicing of tessel edges and vertices, or by actual construction of tessels twisted in space for attachment to such undersides.

By proper remote-splicing of playing-surface edges, a playing surface with the connective properties of a surface with one or more holes may be defined and used. To use the historical chessboard as an example, the players could decide that squares at left and right edges adjoin each other correspondingly, thus transforming the board into the equivalent of a cylinder with the pieces laid out initially at either end. Because the initial layout of the chessboard has its pieces at the two remaining edges, however, the players would not agree to join these edges, since the kings would be in immediate check!

One famous game of MuTou was laid out on a table on which a four-legged chair had been placed. The players painted, rather than scribed, their tessels up the legs of the chair and onto the seat and back; with the altered connectedness of the playing area they obtained some unusual play. Unfortunately, the impossibility of placing the pieces on the vertical tessel surfaces required the use of labels for both tessels and pieces, and the idea met with much resistance for that reason.

Setting Out The Pieces

Before starting the play of the turns, each player privately distributes the shakken among one’s pieces in any way one decides, and sets out all the pieces, unmasking their configuration to the other players for the first time. The players stack their darjarinn on their power pieces.

Each player sets one’s own pieces in the appropriate ‘stand’, or starting area, defined in the scribing; the play of the turns may then begin.

The Opening And Play Of The Turns

The musicians then begin to play, and the first player moves.

In the strictly-competitive form of the game, play continues until only one player is still able to move, and every one of the others has lost the last blood shak. The one remaining player with a blood shak in play is the winner.

In the cooperative forms of the game, play continues until all players agree to stop moving.

Music is stopped only by the musicians, not the players, until the end of the game. When the music stops in mid-game, so does play; when it recommences, so does play.

Capture And Allegiance

A player captures a piece by moving one’s own piece onto the tessel occupied by the piece to be captured. The captured piece is removed from play.

A player changes the allegiance of a target piece, instead of capturing it, by moving one’s own piece as if to capture, replacing the target piece’s identifying cone, and removing the targeting piece from play, in effect trading one’s own piece for the one targeted.

When a piece is removed from play due to capture or change of allegiance, the player carrying out the move may transfer one or more shakken from the removed piece to the piece remaining in play, at a cost of one darjanka per shak transferred.

Allegiance of a piece may be shared, but this feature of the game is too complex to describe here.

Moves, Turns And Music

The bottom bass line determines the rhythm of the moves. One move within a turn must be done in synchrony with one bass beat, and the player moving has as many bass beats to move as one has darjarinn on one’s power piece.

The bottom bass line is often played on a deep drum or a single-string bass viol, and usually comes once in four or five of the song beats, as if marking a measure. The song beats provide the framework for the melodic and harmonic accompaniment for the game.

The accompanists often improvise musical commentary on the moves and turns of the game.

As noted, failure to complete one’s moves within the limit of the number of beats means that the next player in turn may begin the turn before the lagging player completes the remaining moves. Delays by one player do not exempt subsequent players from the requirement to complete their moves at the appropriate points in the pattern of the music, so that moves frequently overlap. Any conflicts arising from delayed moves are resolved in favor of the player most recently reaching the turn; if multiple players have been delayed by one other, the order of precedence in conflicts is from the most recent to the least recent of the players whose turns arise.

Social Dimensions of the Game

To appreciate the role of MuTou in the affairs of a community, one must witness a series of games as an informed guest of the hosting village, family, or coll. Many coll historians, anthropologists, and sociologists subscribe to the idea that MuTou serves to defuse and sublimate a wide range of political and emotional impulses that would otherwise obstruct, damage, or destroy the community’s ability to function effectively. This idea, however, is rejected by governmental and corp authorities and their organizations; govs and corps tend to view MuTou as a major obstacle to the ‘smoothing-in’ of colls with the governing bodies of Tarnus. The debate has raged on in academic centers for centuries, and boils down to whether or not the long-lasting identities and roles of the colls deserve continuation and evolution instead of assimilation and abandonment. This subject is where Yinzaimarr shines; see Vol. III, Book Seven, Chapter 4, “The political entanglements of MuTou.”

Apart from this constant conflict of basic understandings, the game is immensely captivating for everyone caught up in its festivities. Even those in gov or corp service frequently find themselves betting on or even playing in a game when one of their ancestral colls is involved.

Picture a Novander Wye village half a day’s autocart ride outside Purusil, up in the hills, during the fallow season. That’s a good place to start.